The Power of Improv (Or, a Continuation of How I Justify Making Up Damn Near Everything in My Life as I Go Along): Part 1

I was in yoga just a couple weeks ago when a friend of mine

and I began discussing how we frequently find ourselves jumping into situations

with both feet and figuring out how to do things as we go. Obviously, it is

advisable to avoid this method of learning for things such as learning to drive

a car or base-jumping, but it drove home a couple points I’ve always tried to

practice in my regular life. I cannot pack everything I want to say into one

post, so let’s begin with a little back-story and a basic lesson on rule #1 of

improvisation.

As a

self-professed perfectionist at heart, this is something I struggled with as a

child and young teenager. I’ve gotten much better at letting go of some of the

stress and anxiety-inducing perfectionist tendencies over the years, but I

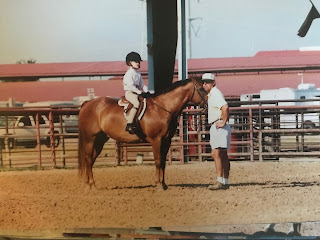

always know they’re still there (note: photo of extremely focused 9 year old self on perfect Candy Bar the pony above). A big aid was the fact that my heart settled

on the sport of horseback riding—it’s impossible to be a perfectionist and

excel in this sport. Animals, at the end of the day, will do animal things, even

if you prepared for 10,000 hours, drove two and a half hours one way, used

every last dime in your name to pay for their well-being, and poured endless

amounts of blood, sweat, and tears into them. You learn to let it slide, or it

drives you straight off the edge into Crazyland. (Chances are you’ll end up

there regardless with horses, but at least try to arrive there safely.)

However,

the only other thing in this world to ever compete with my love for horses was

my interest in theater. One aspect of it that always fascinated me, even as a

young child, was the concept of improv. I remember the first “big” show I was

ever in—I was 7 or 8 years old, and the summer camp at our local theater was

putting on “The Wizard of Oz”. I quite liked the movie, and my brother was into

theater at the time, so my mom signed me up, and I got cast as the scarecrow.

Honestly, it was probably just because I had yellow straw-colored hair, but

whatever. I got to wear a costume and sing and dance on stage, and that’s all I

cared about.

My brother

and I were not quite to our I-Hate-Your-Guts stage in our lives, and I still

thought he was cool, so I welcomed any advice he had for me with open arms. I

had never been in any play beyond the church Christmas plays, and most of the

time we were just screaming Christmas carols at the top of our lungs, so I

didn’t really count that. THIS was the REAL deal.

He’d help

me run lines, and we re-watched “The Wizard of Oz” so I could practice walking

as if I had straw for legs. But one thing he told me stuck with me especially

well—if I forgot my lines, or if one of my friends forgot their lines, my job

was to improv. “Just say something

you think your character would say. Keep pretending to be the scarecrow, and

make it up until you remember the lines again.”

Now THIS

sounded like fun. I wasn’t going to forget MY lines (see “perfectionist”

above), but I was ALWAYS poised and ready to improv on the spot in the event

one of my friends forgot their lines. I was so ready, you could say I almost

hoped for it. Improv sounded fun, and so foreign from my over-prepared

perfectionist self, I couldn’t wait to try it.

I don’t

remember if it ever happened that summer, but the lesson stuck with me for

years to come—just do what you think someone in your situation would do, and

keep doing that until you remember the correct answer again. I stuck with

theater through 8th grade, and moved more towards the technical side

of it through high school before dropping it to go to college and pursue horses

full time. My brother and I grew distant in high school, but a small part of me

always admired his theatrical skills—he and his friends were local celebrities

for their work with our school’s improv team.

As I entered high school and got

older, I began to recede from the theater world—I became acutely aware that I

wasn’t very good, I hated the sound of my own voice, couldn’t make jokes on the

fly, and, frankly, began to develop quite the shy streak among kids my own age.

It wasn’t so much that I avoided interaction, but I started to not enjoy it,

and even would sometimes feel anxious about it. I didn’t have many people I

considered to be good friends in high school, and I’ve never enjoyed having a

big group of “acquaintances”, so I stuck with my small crew of 3 or 4 people,

and just said “screw it” to the rest of the school community. I was basically

invisible to most of my school, and I didn’t mind it that way.

The shyness very quickly broke when

I entered college and was forced to sink or swim—again, drawing on my brother’s

advice to just do what I think I should do until I figured it out, and,

luckily, that led me to meet some of the weirdest, funniest, kindest, most

entertaining people I now get to call my closest friends.

This practice has

landed me countless jobs, and taken me to experiences I never could have

dreamed of, but we’ll get into all that some other day.

The whole concept of improv is this

theory of “yes, and”. The idea is this: If two people are on stage, and one of

them says, “Man, this line is long,” the other should, if following the theory

of improv, say, “Yes, and the box office won’t even open for another 8 hours.”

In this case, the second person has now opened up a door leading to several

other doors in the first person’s story. Now, consider it the other way—person

one: “Man, this line is long.” Person two: “No it’s not, there are only three

of us in line.” Not only has the second person squashed person one’s idea of

there being a long line, but now person one has to scramble to follow along

with person two, the audience has to scramble to figure out whose story to

follow, and person two now has to develop a story with less than ideal backing

as person one tries to figure out where to go. It doesn’t work. When the time

comes to improv, your job is to catch the ball thrown at you, add something to

it, and keep it moving. That cannot be done if you deny the existence and

validity of every story that comes your way.

“Yes, and” is something I’ve been

trying to practice more frequently lately—it’s a little bit along the same

lines as that “Yes Man” movie, except I try to practice a bit more self care so

I’m not making poor choices that lead to a climactic conglomeration of

conflicts.

Keep that in mind. I’m going to

stop here for now, because it’s getting late and a foggy, rainy evening is

calling me to read my book in my bed. So to that, I’m going to say, “Yes, and

I’m going to fall asleep while I’m at it.”

Comments

Post a Comment